diff --git a/site/news/policy.de.md b/site/news/policy.de.md

index 203ab7d..037d059 100644

--- a/site/news/policy.de.md

+++ b/site/news/policy.de.md

@@ -176,3 +176,212 @@ exist, for example, the work done by Sam Zeloof and the Libre Silicon project:

*

(Sam literally makes CPUs in his garage)

+

+Why?

+====

+

+This next section previously existed in a less than diplomatic manner. It

+has been restored, as of August 2024, because the wisdom that it provides is

+important, yet being respectful of our friends in Massachussets is also

+a good thing to do, where feasible. This section was previously deleted, as

+a gesture of good will to this people, but it can't not be here, so without

+further ado:

+

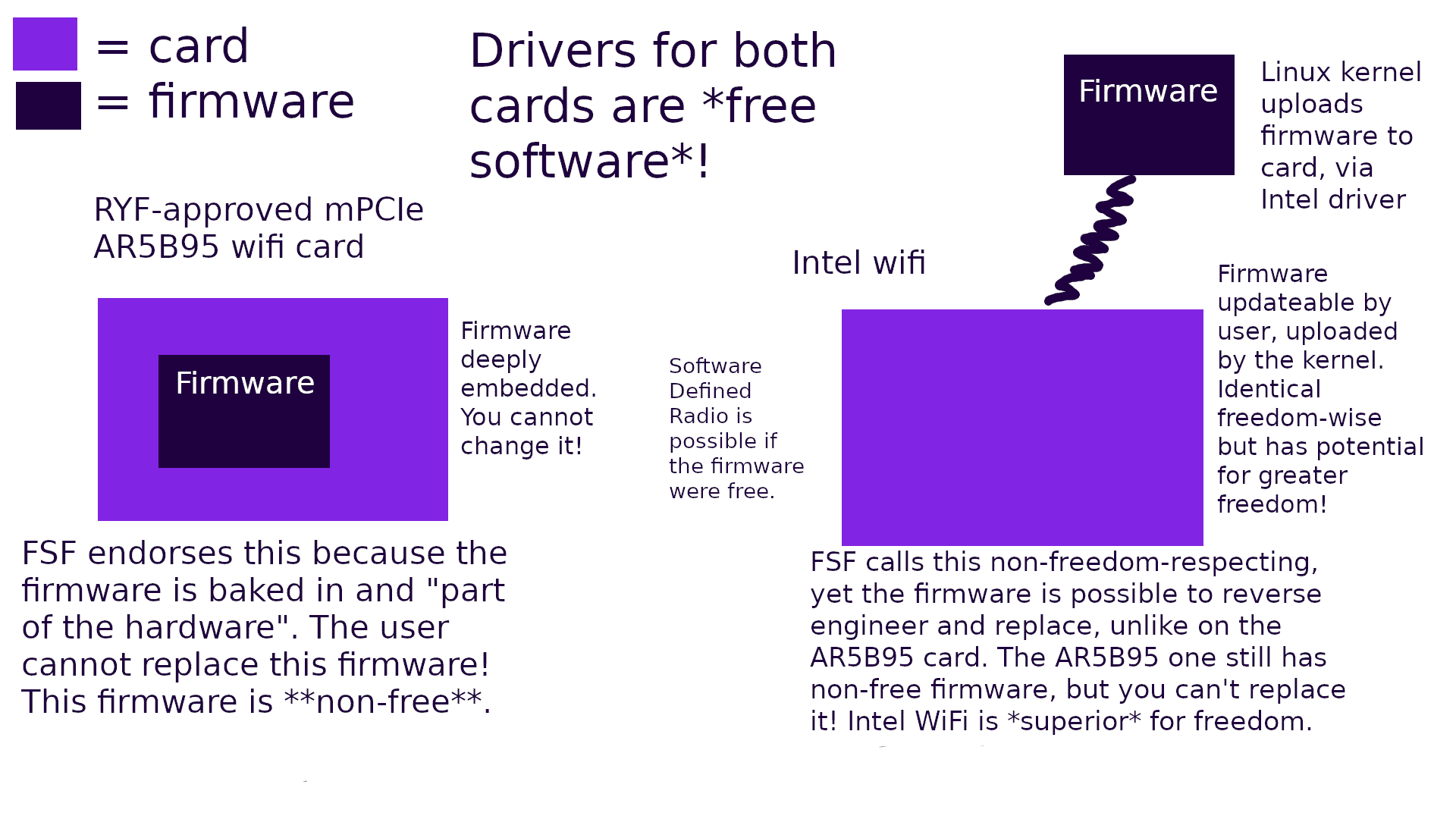

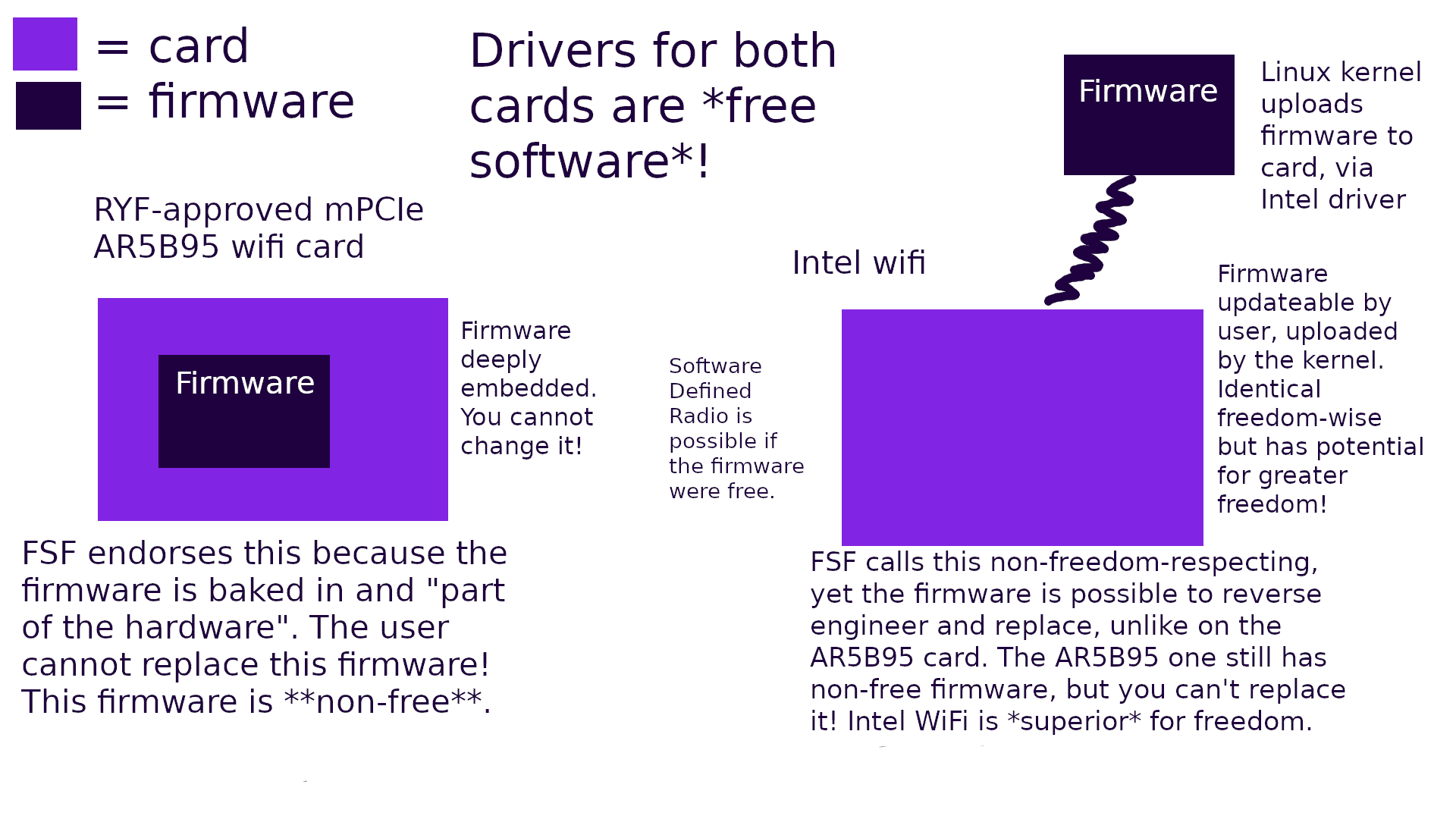

+Firstly, observe the following graphic:

+

+

+

+Why does this policy page need to be written? Isn't it just describing basic

+common sense? The common sense that free software activism must demand all

+software to be free; why even talk about it?

+

+This page has talked about Libreboot's *blob reduction policy*, but more

+context is needed. We need to talk about it, because there are many different

+interpretations for the exact same argument, depending on your point of view.

+

+If you use a piece of hardware in Linux, and it works, you might see that it has

+free drivers and think nothing else. You will run free application software

+such as Firefox, Vim, KDE Plasma desktop, and everything is wonderful, right?

+

+Where drivers and applications (and your operating system) are concerned, this

+is much clearer, because it's software that you're running on your main CPU,

+that you installed yourself. What of firmware?

+

+Libreboot is not the only firmware that exists on your machine, when you have

+Libreboot. Look at these articles, which cover other firmwares:

+

+*

+*

+

+You may ask: should the other firmwares be free too? The answer is **yes**, but

+it's complicated: it's not always practical to even study those firmwares. For

+example, there are so many webcams out there, so many SSDs, so many devices

+all doing the same thing, but implemented differently. Coreboot is already

+hard enough, and there are so many mainboards out there.

+

+For example: every SSD has its own controller, and it has to do a lot of

+error correction at great speed, to mitigate the inherent unreliability of

+NAND flash. This firmware is highly specialised, and tailored to *that* SSD;

+not merely that SSD product line, but *that* SSD, because it often has to be

+tweaked per SSD; ditto SD cards, which fundamentally use the same technology.

+Would it be practical for something like Linux to provide firmware for

+absolutely every SSD? No. Absolutely not; and this is actually an example of

+where it makes more sense to bake the firmware into the hardware, rather than

+supply it as a firmware in Linux (even if the firmware is updateable, which it

+is on some SSDs).

+

+Another example: your wireless card implements a software defined radio, to

+implement all of the various WiFi protocols, which is what your WiFi drivers

+make use of. The drivers themselves are also quite complicated. However, the

+same driver might be able to operate multiple wireless cards, if there is

+some standard interface (regardless of whether it's documented), that the

+same driver can use between all the cards, even if those cards are all very

+different; this is where firmware comes in.

+

+Coreboot only covers the main boot firmware, but you will have other firmware

+running on your machine. It's simply a fact.

+

+Historically, a lot of hardware has firmware baked into it, which does whatever

+it does on that piece of hardware (e.g. software defined radio on a wifi

+device, firmware implementing an AHCI interface for your SATA SSD).

+

+In some cases, you will find that this firmware is *not* baked into the device.

+Instead, a firmware is provided in Linux, uploaded to the device at boot

+time, and this must be performed every time you boot or every time you plug

+in that device.

+

+Having firmware in Linux is *good*. Proprietary software is also *bad*, so why

+is having *more* proprietary firmware in Linux *good*? Surely, free firmware

+would be better, but this firmware has never been free; typically, most

+firmware has been non-free, but baked into the hardware so you just didn't

+see it. We can demand that the vendors release source code, and we do; in some

+cases, we even succeed (for example `ath9k_htc` WiFi dongles have free firmware

+available in Linux).

+

+The reason vendors put more firmware in Linux nowadays is it's cheaper. If the

+device itself has firmware baked in, then more money is spent on the EEPROM

+that stores it, and it makes research/development more expensive; having an

+easy software update mechanism allows bugs to be fixed more quickly, during

+development and post-release, thus reducing costs. This saves the

+industry *billions*, and it is actually of benefit to the free software

+community, because it makes reverse engineering easier, and it makes

+actually updating the firmware easier, so more proprietary software can

+actually be *replaced with free software*. If some standard interface exists,

+for the firmware, then that makes reverse engineering easier *across many

+devices*, instead of just one.

+

+Hardware is also very complex, more so now than in the past; having the

+hardware be flexible, configured by *firmware*, makes it easier to work

+around defects in the hardware. For example, if a circuit for a new feature

+is quite buggy on a bit of hardware, but could be turned off without ill

+consequence, a firmware update might do exactly that.

+

+The existence of such firmware also reminds more people of that fact, so more

+people are likely to demand free software. If the firmware is *hidden in the

+hardware*, fewer people are likely to raise a stink about it. We in the

+Libreboot project want all firmware to be free, and we've known of this

+problem for years.

+

+Some people take what we call the *head in the sand* approach, where any and

+all software in Linux must be excluded; certain distros out there do this, and

+it is an entirely misguided approach. It is misguided, precisely because it

+tells people that *compatible* hardware is more free, when it isn't; more

+likely, any hardware that works (without firmware in Linux) likely just has

+that same firmware baked into it; in other words, hidden from the user. Hence

+the *head in the sand approach* - and this approach would result in far less

+hardware being supported.

+

+Libreboot previously had its head in the sand, before November 2022. Since

+November 2022, Libreboot has been much more pragmatic, implementing the

+policy that you read now, instead of simply banning all proprietary firmware;

+the result is increased hardware support, and in practise many of the newer

+machines we support are still entirely free in coreboot (including memory

+controller initialisation), right up to Intel Haswell generation.

+

+You are advised not to put your head in the sand. Better to see the world as

+it is, and here is the actual world as it is:

+

+These firmwares are *required*. In some cases, hardware might have firmware

+baked in but provide an update mechanism, e.g. CPU microcode update

+mechanism. These firmware updates fix security bugs, reliability issues,

+and in some cases even *safety issues* (e.g. thermal safety on a CPU fixed by a

+microcode update).

+

+Baking firmware into the device means that the firmware is less likely to be

+seen by the user, so fewer people are likely to raise a fuss about it; if

+the main boot firmware for example was baked into the PCH on your Intel

+system, completely non-replaceable or even inaccessible, fewer people would

+demand free boot firmware and a project like coreboot (and by extension

+Libreboot) may not even exist!

+

+Such is the paradox of free firmware development. Libreboot previously took

+a much more hardline approach, banning absolutely all proprietary firmware

+whatsoever; the result was that far fewer machines could be supported. A more

+pragmatic policy, the one you've just read, was introduced in November 2022,

+in an effort to support more hardware and therefore increase the number of

+coreboot users; by extension, this will lead to more coreboot development,

+and more proprietary firmware being replaced with free software.

+

+Facts are facts; how you handle them is where the magic happens, and Libreboot

+has made its choice. The result since November 2022 has indeed been more

+coreboot users, and a lot more hardware supported; more hardware has been

+ported to coreboot, that might not have even been ported in the first place,

+e.g. more Dell Latitude laptops are supported now (basically all of the

+IvyBridge and SandyBridge ones).

+

+The four freedoms are absolute, but the road to freedom is never a straight

+line. Libreboot's policies are laser-focused on getting to that final goal,

+but without being dogmatic. By being flexible, while pushing for more firmware

+to be freed, more firmware is freed. It's as simple as that. We don't want

+proprietary software at all, but in order to have less of it, we have to

+have more - for now.

+

+Let's take an extreme example: what if coreboot was entirely binary blobs

+for a given mainboard? Coreboot itself only initialises the hardware, and

+jumps to a payload in the flash; in this case, the payload (e.g. GNU GRUB)

+would still be free software. Surely, all free firmware would be better,

+but this is still an improvement over the original vendor firmware. The

+original vendor firmware will have non-free boot firmware *and* its analog

+of a coreboot payload (typically a UEFI implementation running various

+applications via DXEs) would be non-free. *Coreboot does* in fact do this

+on many newer Intel and AMD platforms, all of which Libreboot intends to

+accomodate in the future, and doing so would absolutely comply with this

+very policy that you are reading now, namely the Binary Blob Reduction Policy.

+

+You can bet we'll tell everyone that Intel FSP is bad and should be replaced

+with free software, and we do; many Intel blobs have in fact been replaced

+with Free Software. For example, Libreboot previously provided Intel MRC

+which is a raminit blob, on Intel Haswell machines. Angel Pons reverse

+engineered the MRC and wrote native memory controller initialisation (raminit)

+on this platform, which Libreboot now uses instead of MRC.

+

+This is a delicate balance, that a lot of projects get wrong - they will

+accept blobs, and *not* talk about them. In Libreboot, it's the exact

+opposite: we make sure you know about them, and tell you that they are bad,

+and we say that they should be fully replaced.

+

+Unlike some in the community, we even advocate for free software in cases

+where the software can't actually be replaced. For example: the RP2040 Boot ROM

+is free software, with public source code:

+

+

+

+This is the boot ROM source code for RP2040 devices such as Raspberry Pi Pico.

+It is a reprogrammable device, and we even use it as a

+cheap [SPI flasher](../docs/install/spi.md) running `pico-serprog`. The

+main firmware is replaceable, but the *boot ROM* is read-only on this machine;

+there are some people would would not insist on free software at that level,

+despite being free software activists, because they would regard the boot

+ROM as "part of the hardware" - in Libreboot, we insist that all such

+software, including this, be free. Freedom merely to study the source code

+is still an important freedom, and someone might make a replica of the

+hardware at some point; if they do, that boot ROM source code is there for

+them to use, without having to re-implement it themselves. Isn't that great?

+

+I hope that these examples might inspire some people to take more action in

+demanding free software everywhere, and to enlighten more people on the road

+to software freedom. The road Libreboot takes is the one less traveled, the

+one of pragmatism without compromise; we will not lose sight of our original

+goals, namely absolute computer user freedom.

+

+The article will end here, because anything else would be more rambling.

diff --git a/site/news/policy.md b/site/news/policy.md

index b2e6b29..1686f9f 100644

--- a/site/news/policy.md

+++ b/site/news/policy.md

@@ -168,3 +168,212 @@ exist, for example, the work done by Sam Zeloof and the Libre Silicon project:

*

(Sam literally makes CPUs in his garage)

+

+Why?

+====

+

+This next section previously existed in a less than diplomatic manner. It

+has been restored, as of August 2024, because the wisdom that it provides is

+important, yet being respectful of our friends in Massachussets is also

+a good thing to do, where feasible. This section was previously deleted, as

+a gesture of good will to this people, but it can't not be here, so without

+further ado:

+

+Firstly, observe the following graphic:

+

+

+

+Why does this policy page need to be written? Isn't it just describing basic

+common sense? The common sense that free software activism must demand all

+software to be free; why even talk about it?

+

+This page has talked about Libreboot's *blob reduction policy*, but more

+context is needed. We need to talk about it, because there are many different

+interpretations for the exact same argument, depending on your point of view.

+

+If you use a piece of hardware in Linux, and it works, you might see that it has

+free drivers and think nothing else. You will run free application software

+such as Firefox, Vim, KDE Plasma desktop, and everything is wonderful, right?

+

+Where drivers and applications (and your operating system) are concerned, this

+is much clearer, because it's software that you're running on your main CPU,

+that you installed yourself. What of firmware?

+

+Libreboot is not the only firmware that exists on your machine, when you have

+Libreboot. Look at these articles, which cover other firmwares:

+

+*

+*

+

+You may ask: should the other firmwares be free too? The answer is **yes**, but

+it's complicated: it's not always practical to even study those firmwares. For

+example, there are so many webcams out there, so many SSDs, so many devices

+all doing the same thing, but implemented differently. Coreboot is already

+hard enough, and there are so many mainboards out there.

+

+For example: every SSD has its own controller, and it has to do a lot of

+error correction at great speed, to mitigate the inherent unreliability of

+NAND flash. This firmware is highly specialised, and tailored to *that* SSD;

+not merely that SSD product line, but *that* SSD, because it often has to be

+tweaked per SSD; ditto SD cards, which fundamentally use the same technology.

+Would it be practical for something like Linux to provide firmware for

+absolutely every SSD? No. Absolutely not; and this is actually an example of

+where it makes more sense to bake the firmware into the hardware, rather than

+supply it as a firmware in Linux (even if the firmware is updateable, which it

+is on some SSDs).

+

+Another example: your wireless card implements a software defined radio, to

+implement all of the various WiFi protocols, which is what your WiFi drivers

+make use of. The drivers themselves are also quite complicated. However, the

+same driver might be able to operate multiple wireless cards, if there is

+some standard interface (regardless of whether it's documented), that the

+same driver can use between all the cards, even if those cards are all very

+different; this is where firmware comes in.

+

+Coreboot only covers the main boot firmware, but you will have other firmware

+running on your machine. It's simply a fact.

+

+Historically, a lot of hardware has firmware baked into it, which does whatever

+it does on that piece of hardware (e.g. software defined radio on a wifi

+device, firmware implementing an AHCI interface for your SATA SSD).

+

+In some cases, you will find that this firmware is *not* baked into the device.

+Instead, a firmware is provided in Linux, uploaded to the device at boot

+time, and this must be performed every time you boot or every time you plug

+in that device.

+

+Having firmware in Linux is *good*. Proprietary software is also *bad*, so why

+is having *more* proprietary firmware in Linux *good*? Surely, free firmware

+would be better, but this firmware has never been free; typically, most

+firmware has been non-free, but baked into the hardware so you just didn't

+see it. We can demand that the vendors release source code, and we do; in some

+cases, we even succeed (for example `ath9k_htc` WiFi dongles have free firmware

+available in Linux).

+

+The reason vendors put more firmware in Linux nowadays is it's cheaper. If the

+device itself has firmware baked in, then more money is spent on the EEPROM

+that stores it, and it makes research/development more expensive; having an

+easy software update mechanism allows bugs to be fixed more quickly, during

+development and post-release, thus reducing costs. This saves the

+industry *billions*, and it is actually of benefit to the free software

+community, because it makes reverse engineering easier, and it makes

+actually updating the firmware easier, so more proprietary software can

+actually be *replaced with free software*. If some standard interface exists,

+for the firmware, then that makes reverse engineering easier *across many

+devices*, instead of just one.

+

+Hardware is also very complex, more so now than in the past; having the

+hardware be flexible, configured by *firmware*, makes it easier to work

+around defects in the hardware. For example, if a circuit for a new feature

+is quite buggy on a bit of hardware, but could be turned off without ill

+consequence, a firmware update might do exactly that.

+

+The existence of such firmware also reminds more people of that fact, so more

+people are likely to demand free software. If the firmware is *hidden in the

+hardware*, fewer people are likely to raise a stink about it. We in the

+Libreboot project want all firmware to be free, and we've known of this

+problem for years.

+

+Some people take what we call the *head in the sand* approach, where any and

+all software in Linux must be excluded; certain distros out there do this, and

+it is an entirely misguided approach. It is misguided, precisely because it

+tells people that *compatible* hardware is more free, when it isn't; more

+likely, any hardware that works (without firmware in Linux) likely just has

+that same firmware baked into it; in other words, hidden from the user. Hence

+the *head in the sand approach* - and this approach would result in far less

+hardware being supported.

+

+Libreboot previously had its head in the sand, before November 2022. Since

+November 2022, Libreboot has been much more pragmatic, implementing the

+policy that you read now, instead of simply banning all proprietary firmware;

+the result is increased hardware support, and in practise many of the newer

+machines we support are still entirely free in coreboot (including memory

+controller initialisation), right up to Intel Haswell generation.

+

+You are advised not to put your head in the sand. Better to see the world as

+it is, and here is the actual world as it is:

+

+These firmwares are *required*. In some cases, hardware might have firmware

+baked in but provide an update mechanism, e.g. CPU microcode update

+mechanism. These firmware updates fix security bugs, reliability issues,

+and in some cases even *safety issues* (e.g. thermal safety on a CPU fixed by a

+microcode update).

+

+Baking firmware into the device means that the firmware is less likely to be

+seen by the user, so fewer people are likely to raise a fuss about it; if

+the main boot firmware for example was baked into the PCH on your Intel

+system, completely non-replaceable or even inaccessible, fewer people would

+demand free boot firmware and a project like coreboot (and by extension

+Libreboot) may not even exist!

+

+Such is the paradox of free firmware development. Libreboot previously took

+a much more hardline approach, banning absolutely all proprietary firmware

+whatsoever; the result was that far fewer machines could be supported. A more

+pragmatic policy, the one you've just read, was introduced in November 2022,

+in an effort to support more hardware and therefore increase the number of

+coreboot users; by extension, this will lead to more coreboot development,

+and more proprietary firmware being replaced with free software.

+

+Facts are facts; how you handle them is where the magic happens, and Libreboot

+has made its choice. The result since November 2022 has indeed been more

+coreboot users, and a lot more hardware supported; more hardware has been

+ported to coreboot, that might not have even been ported in the first place,

+e.g. more Dell Latitude laptops are supported now (basically all of the

+IvyBridge and SandyBridge ones).

+

+The four freedoms are absolute, but the road to freedom is never a straight

+line. Libreboot's policies are laser-focused on getting to that final goal,

+but without being dogmatic. By being flexible, while pushing for more firmware

+to be freed, more firmware is freed. It's as simple as that. We don't want

+proprietary software at all, but in order to have less of it, we have to

+have more - for now.

+

+Let's take an extreme example: what if coreboot was entirely binary blobs

+for a given mainboard? Coreboot itself only initialises the hardware, and

+jumps to a payload in the flash; in this case, the payload (e.g. GNU GRUB)

+would still be free software. Surely, all free firmware would be better,

+but this is still an improvement over the original vendor firmware. The

+original vendor firmware will have non-free boot firmware *and* its analog

+of a coreboot payload (typically a UEFI implementation running various

+applications via DXEs) would be non-free. *Coreboot does* in fact do this

+on many newer Intel and AMD platforms, all of which Libreboot intends to

+accomodate in the future, and doing so would absolutely comply with this

+very policy that you are reading now, namely the Binary Blob Reduction Policy.

+

+You can bet we'll tell everyone that Intel FSP is bad and should be replaced

+with free software, and we do; many Intel blobs have in fact been replaced

+with Free Software. For example, Libreboot previously provided Intel MRC

+which is a raminit blob, on Intel Haswell machines. Angel Pons reverse

+engineered the MRC and wrote native memory controller initialisation (raminit)

+on this platform, which Libreboot now uses instead of MRC.

+

+This is a delicate balance, that a lot of projects get wrong - they will

+accept blobs, and *not* talk about them. In Libreboot, it's the exact

+opposite: we make sure you know about them, and tell you that they are bad,

+and we say that they should be fully replaced.

+

+Unlike some in the community, we even advocate for free software in cases

+where the software can't actually be replaced. For example: the RP2040 Boot ROM

+is free software, with public source code:

+

+

+

+This is the boot ROM source code for RP2040 devices such as Raspberry Pi Pico.

+It is a reprogrammable device, and we even use it as a

+cheap [SPI flasher](../docs/install/spi.md) running `pico-serprog`. The

+main firmware is replaceable, but the *boot ROM* is read-only on this machine;

+there are some people would would not insist on free software at that level,

+despite being free software activists, because they would regard the boot

+ROM as "part of the hardware" - in Libreboot, we insist that all such

+software, including this, be free. Freedom merely to study the source code

+is still an important freedom, and someone might make a replica of the

+hardware at some point; if they do, that boot ROM source code is there for

+them to use, without having to re-implement it themselves. Isn't that great?

+

+I hope that these examples might inspire some people to take more action in

+demanding free software everywhere, and to enlighten more people on the road

+to software freedom. The road Libreboot takes is the one less traveled, the

+one of pragmatism without compromise; we will not lose sight of our original

+goals, namely absolute computer user freedom.

+

+The article will end here, because anything else would be more rambling.

diff --git a/site/news/policy.uk.md b/site/news/policy.uk.md

index ad25505..4ba7616 100644

--- a/site/news/policy.uk.md

+++ b/site/news/policy.uk.md

@@ -170,3 +170,212 @@ Libreboot вирішує цю ситуацію *суворо* та *принци

*

(Сем буквально виробляє процесори в своєму гаражі)

+

+Why?

+====

+

+This next section previously existed in a less than diplomatic manner. It

+has been restored, as of August 2024, because the wisdom that it provides is

+important, yet being respectful of our friends in Massachussets is also

+a good thing to do, where feasible. This section was previously deleted, as

+a gesture of good will to this people, but it can't not be here, so without

+further ado:

+

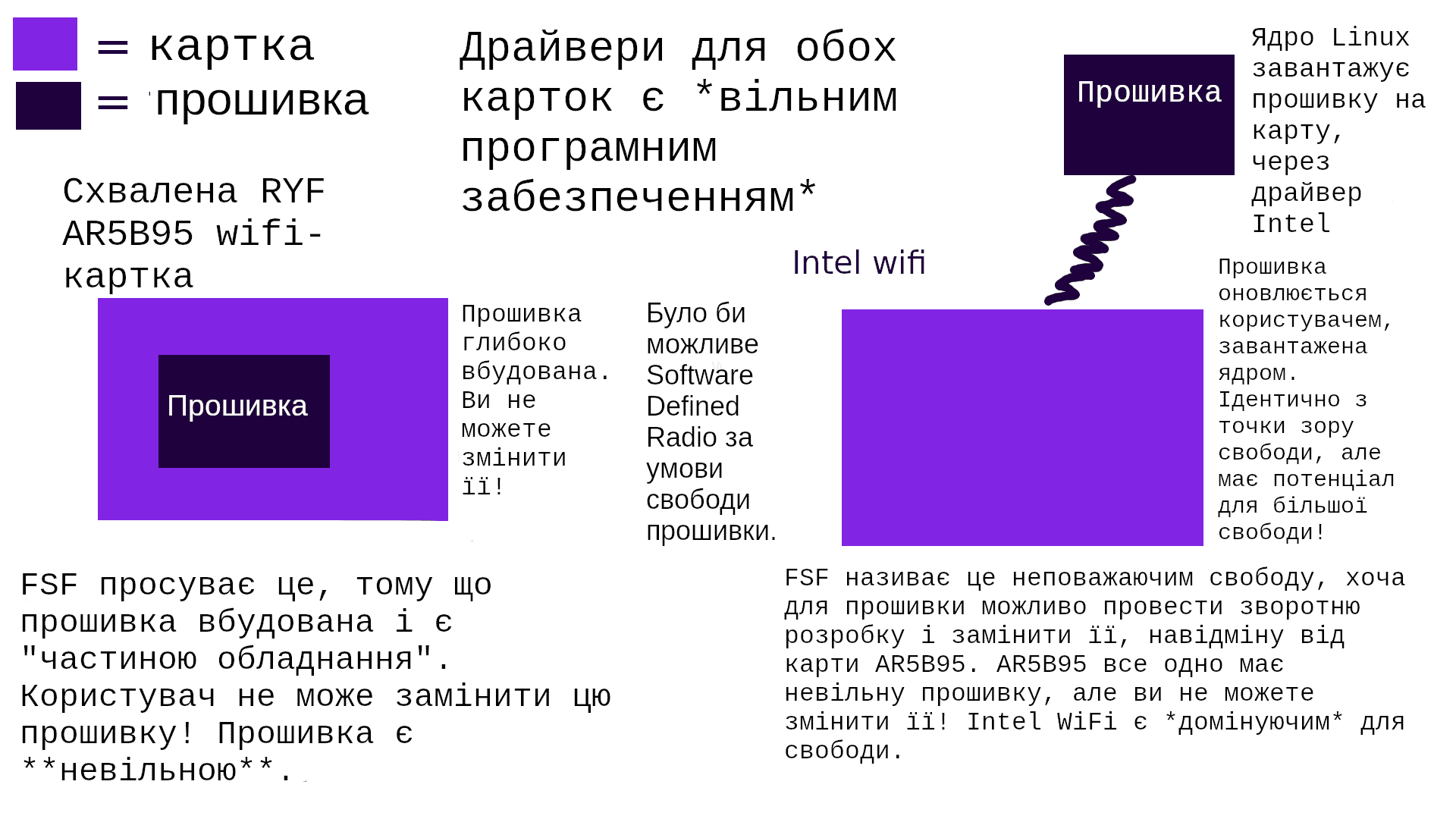

+Firstly, observe the following graphic:

+

+

+

+Why does this policy page need to be written? Isn't it just describing basic

+common sense? The common sense that free software activism must demand all

+software to be free; why even talk about it?

+

+This page has talked about Libreboot's *blob reduction policy*, but more

+context is needed. We need to talk about it, because there are many different

+interpretations for the exact same argument, depending on your point of view.

+

+If you use a piece of hardware in Linux, and it works, you might see that it has

+free drivers and think nothing else. You will run free application software

+such as Firefox, Vim, KDE Plasma desktop, and everything is wonderful, right?

+

+Where drivers and applications (and your operating system) are concerned, this

+is much clearer, because it's software that you're running on your main CPU,

+that you installed yourself. What of firmware?

+

+Libreboot is not the only firmware that exists on your machine, when you have

+Libreboot. Look at these articles, which cover other firmwares:

+

+*

+*

+

+You may ask: should the other firmwares be free too? The answer is **yes**, but

+it's complicated: it's not always practical to even study those firmwares. For

+example, there are so many webcams out there, so many SSDs, so many devices

+all doing the same thing, but implemented differently. Coreboot is already

+hard enough, and there are so many mainboards out there.

+

+For example: every SSD has its own controller, and it has to do a lot of

+error correction at great speed, to mitigate the inherent unreliability of

+NAND flash. This firmware is highly specialised, and tailored to *that* SSD;

+not merely that SSD product line, but *that* SSD, because it often has to be

+tweaked per SSD; ditto SD cards, which fundamentally use the same technology.

+Would it be practical for something like Linux to provide firmware for

+absolutely every SSD? No. Absolutely not; and this is actually an example of

+where it makes more sense to bake the firmware into the hardware, rather than

+supply it as a firmware in Linux (even if the firmware is updateable, which it

+is on some SSDs).

+

+Another example: your wireless card implements a software defined radio, to

+implement all of the various WiFi protocols, which is what your WiFi drivers

+make use of. The drivers themselves are also quite complicated. However, the

+same driver might be able to operate multiple wireless cards, if there is

+some standard interface (regardless of whether it's documented), that the

+same driver can use between all the cards, even if those cards are all very

+different; this is where firmware comes in.

+

+Coreboot only covers the main boot firmware, but you will have other firmware

+running on your machine. It's simply a fact.

+

+Historically, a lot of hardware has firmware baked into it, which does whatever

+it does on that piece of hardware (e.g. software defined radio on a wifi

+device, firmware implementing an AHCI interface for your SATA SSD).

+

+In some cases, you will find that this firmware is *not* baked into the device.

+Instead, a firmware is provided in Linux, uploaded to the device at boot

+time, and this must be performed every time you boot or every time you plug

+in that device.

+

+Having firmware in Linux is *good*. Proprietary software is also *bad*, so why

+is having *more* proprietary firmware in Linux *good*? Surely, free firmware

+would be better, but this firmware has never been free; typically, most

+firmware has been non-free, but baked into the hardware so you just didn't

+see it. We can demand that the vendors release source code, and we do; in some

+cases, we even succeed (for example `ath9k_htc` WiFi dongles have free firmware

+available in Linux).

+

+The reason vendors put more firmware in Linux nowadays is it's cheaper. If the

+device itself has firmware baked in, then more money is spent on the EEPROM

+that stores it, and it makes research/development more expensive; having an

+easy software update mechanism allows bugs to be fixed more quickly, during

+development and post-release, thus reducing costs. This saves the

+industry *billions*, and it is actually of benefit to the free software

+community, because it makes reverse engineering easier, and it makes

+actually updating the firmware easier, so more proprietary software can

+actually be *replaced with free software*. If some standard interface exists,

+for the firmware, then that makes reverse engineering easier *across many

+devices*, instead of just one.

+

+Hardware is also very complex, more so now than in the past; having the

+hardware be flexible, configured by *firmware*, makes it easier to work

+around defects in the hardware. For example, if a circuit for a new feature

+is quite buggy on a bit of hardware, but could be turned off without ill

+consequence, a firmware update might do exactly that.

+

+The existence of such firmware also reminds more people of that fact, so more

+people are likely to demand free software. If the firmware is *hidden in the

+hardware*, fewer people are likely to raise a stink about it. We in the

+Libreboot project want all firmware to be free, and we've known of this

+problem for years.

+

+Some people take what we call the *head in the sand* approach, where any and

+all software in Linux must be excluded; certain distros out there do this, and

+it is an entirely misguided approach. It is misguided, precisely because it

+tells people that *compatible* hardware is more free, when it isn't; more

+likely, any hardware that works (without firmware in Linux) likely just has

+that same firmware baked into it; in other words, hidden from the user. Hence

+the *head in the sand approach* - and this approach would result in far less

+hardware being supported.

+

+Libreboot previously had its head in the sand, before November 2022. Since

+November 2022, Libreboot has been much more pragmatic, implementing the

+policy that you read now, instead of simply banning all proprietary firmware;

+the result is increased hardware support, and in practise many of the newer

+machines we support are still entirely free in coreboot (including memory

+controller initialisation), right up to Intel Haswell generation.

+

+You are advised not to put your head in the sand. Better to see the world as

+it is, and here is the actual world as it is:

+

+These firmwares are *required*. In some cases, hardware might have firmware

+baked in but provide an update mechanism, e.g. CPU microcode update

+mechanism. These firmware updates fix security bugs, reliability issues,

+and in some cases even *safety issues* (e.g. thermal safety on a CPU fixed by a

+microcode update).

+

+Baking firmware into the device means that the firmware is less likely to be

+seen by the user, so fewer people are likely to raise a fuss about it; if

+the main boot firmware for example was baked into the PCH on your Intel

+system, completely non-replaceable or even inaccessible, fewer people would

+demand free boot firmware and a project like coreboot (and by extension

+Libreboot) may not even exist!

+

+Such is the paradox of free firmware development. Libreboot previously took

+a much more hardline approach, banning absolutely all proprietary firmware

+whatsoever; the result was that far fewer machines could be supported. A more

+pragmatic policy, the one you've just read, was introduced in November 2022,

+in an effort to support more hardware and therefore increase the number of

+coreboot users; by extension, this will lead to more coreboot development,

+and more proprietary firmware being replaced with free software.

+

+Facts are facts; how you handle them is where the magic happens, and Libreboot

+has made its choice. The result since November 2022 has indeed been more

+coreboot users, and a lot more hardware supported; more hardware has been

+ported to coreboot, that might not have even been ported in the first place,

+e.g. more Dell Latitude laptops are supported now (basically all of the

+IvyBridge and SandyBridge ones).

+

+The four freedoms are absolute, but the road to freedom is never a straight

+line. Libreboot's policies are laser-focused on getting to that final goal,

+but without being dogmatic. By being flexible, while pushing for more firmware

+to be freed, more firmware is freed. It's as simple as that. We don't want

+proprietary software at all, but in order to have less of it, we have to

+have more - for now.

+

+Let's take an extreme example: what if coreboot was entirely binary blobs

+for a given mainboard? Coreboot itself only initialises the hardware, and

+jumps to a payload in the flash; in this case, the payload (e.g. GNU GRUB)

+would still be free software. Surely, all free firmware would be better,

+but this is still an improvement over the original vendor firmware. The

+original vendor firmware will have non-free boot firmware *and* its analog

+of a coreboot payload (typically a UEFI implementation running various

+applications via DXEs) would be non-free. *Coreboot does* in fact do this

+on many newer Intel and AMD platforms, all of which Libreboot intends to

+accomodate in the future, and doing so would absolutely comply with this

+very policy that you are reading now, namely the Binary Blob Reduction Policy.

+

+You can bet we'll tell everyone that Intel FSP is bad and should be replaced

+with free software, and we do; many Intel blobs have in fact been replaced

+with Free Software. For example, Libreboot previously provided Intel MRC

+which is a raminit blob, on Intel Haswell machines. Angel Pons reverse

+engineered the MRC and wrote native memory controller initialisation (raminit)

+on this platform, which Libreboot now uses instead of MRC.

+

+This is a delicate balance, that a lot of projects get wrong - they will

+accept blobs, and *not* talk about them. In Libreboot, it's the exact

+opposite: we make sure you know about them, and tell you that they are bad,

+and we say that they should be fully replaced.

+

+Unlike some in the community, we even advocate for free software in cases

+where the software can't actually be replaced. For example: the RP2040 Boot ROM

+is free software, with public source code:

+

+

+

+This is the boot ROM source code for RP2040 devices such as Raspberry Pi Pico.

+It is a reprogrammable device, and we even use it as a

+cheap [SPI flasher](../docs/install/spi.md) running `pico-serprog`. The

+main firmware is replaceable, but the *boot ROM* is read-only on this machine;

+there are some people would would not insist on free software at that level,

+despite being free software activists, because they would regard the boot

+ROM as "part of the hardware" - in Libreboot, we insist that all such

+software, including this, be free. Freedom merely to study the source code

+is still an important freedom, and someone might make a replica of the

+hardware at some point; if they do, that boot ROM source code is there for

+them to use, without having to re-implement it themselves. Isn't that great?

+

+I hope that these examples might inspire some people to take more action in

+demanding free software everywhere, and to enlighten more people on the road

+to software freedom. The road Libreboot takes is the one less traveled, the

+one of pragmatism without compromise; we will not lose sight of our original

+goals, namely absolute computer user freedom.

+

+The article will end here, because anything else would be more rambling.