29 KiB

% Binäre Blob Reduktions Richtlinie % Leah Rowe % 4 January 2022 (updated 15 November 2022)

Einleitung

Dieser Artikel beschreibt die Prinzipien die das Libreboot Projekt definieren. Für Informationen darüber wie diese Prinzipien in der Praxis angewendet werden, bitte lies diesen Artikel stattdessen: Software and hardware freedom status for each mainboard supported by Libreboot

Libreboot's Richtlinie ist für jeden Benutzer so viel Software Freiheit zu bieten wie möglich, auf jeglichem Bit von unterstützter Hardware, und so viel Hardware von Coreboot zu unterstützen wie möglich; was dies bedeutet ist, dass Du die Möglichkeit haben solltest, jeglichen Quelltext, jegliche Dokumentation oder jegliche andere Ressource die Libreboot zu dem machen was es ist, zu lesen, zu modifizieren und zu teilen. Einfach geasgt, Du solltest Kontrolle haben über deine eigene Computernutzung.

Das Ziel von Libreboot ist es genau dies zu ermöglichen, und möglichst vielen Benutzern zu helfen, mittels Automation der Konfiguration, Kompilierung und Installation von coreboot für technisch-unerfahrene Benutzer, und dies weiter zu vereinfachen für den durchschnittlichen Benutzer indem benutzerfreundliche Anleitungen für alles zur Verfügung gestellt werden. Grundsätzlich, Libreboot ist eine coreboot Distribution, ähnlich wie Alpine Linux eine Linux Distribution ist!

Der Zweck diese Dokuments ist, zu skizzieren wie dies erzielt wird, und wie das Projekt auf dieser Basis operiert. Dieses Dokument ist hauptsächlich über die Ideologie und ist daher (größtenteils) nicht-technisch; für technische Informationen schau in die Libreboot build system documentation.

Derzeitiger Projektrahmen

Das Libreboot Projekt ist besorgt um das was in den Haupt Boot Flash IC geht, aber es gibt andere Firmware Teile welche in Betracht gezogen werden sollten, wie erläutert im libreboot FAQ.

Die kritischsten hiervon sind:

- Embedded controller firmware

- HDD/SSD firmware

- Intel Management Engine / AMD PSP firmware

Was ist ein binärer Blob?

Ein binärer Blob, in diesem Zusammenhang, ist jegliches Ausführbares für welches kein Quelltext existiert, welchen Du nicht in einer angemessenen Form lesen und modifizieren darfst. Per Definition sind all diese Blobs proprietärer Natur und sollten vermieden werden.

Bestimmte binäre Blobs sind ebenso problematisch, auf den meisten Coreboot Systemen, aber sie unterscheiden sich von Maschine zu Maschine. Lies mehr unter FAQ, oder auf dieser Seite wie wir mit diesen binären Blobs im Libreboot Projekt umgehen.

Für Informationen über die Intel Management Engine und AMD PSP, schau unter FAQ.

Blob reduction policy

Default configurations

Coreboot, upon which Libreboot is based, is mostly libre software but does require vendor files on some platforms. A most common example might be raminit (memory controller initialisation) or video framebuffer initialisation. The coreboot firmware uses certain vendor code for some of these tasks, on some mainboards, but some mainboards from coreboot can be initialised with 100% libre source code, which you can inspect, and compile for your use.

Libreboot deals with this situation in a strict and principled way. The nature of this is what you're about to read.

The libreboot project has the following policy:

- If free software can be used, it should be used. For example, if VGA ROM initialization otherwise does a better job but coreboot has libre init code for a given graphics device, that code should be used in libreboot, when building a ROM image. Similarly, if memory controller initialization is possible with vendor code or libre code in coreboot, the libre code should be used in ROMs built by the Libreboot build system, and the vendor raminit code should not be used; however, if no libre init code is available for said raminit, it is permitted and Libreboot build system will use the vendor code.

- Some nuance is to be observed: on some laptop or desktop configurations, it's common that there will be two graphics devices (for example, an nvidia and an intel chip, using nvidia optimus technology, on a laptop). It may be that one of them has libre init code in coreboot, but the other one does not. It's perfectly acceptable, and desirable, for libreboot to support both devices, and accomodate the required vendor code on the one that lacks native initialization.

- An exception is made for CPU microcode updates: they are permitted, and in fact required as per libreboot policy. These updates fix CPU bugs, including security bugs, and since the CPU already has non-libre microcode burned into ROM anyway, the only choice is either x86 or broken x86. Thus, libreboot will only allow coreboot mainboard configurations where microcode updates are enabled, if available for the CPU on that mainboard. Releases after 20230423 will provide separate ROM images with microcode excluded, alongside the default ones that include microcode.

- Intel Management Engine: in the libreboot documentation, words must be written

to tell people how to neuter the ME, if possible on a given board.

The

me_cleanerprogram is very useful, and provides a much more secure ME configuration. - Vendor blobs should never be deleted, even if they are unused. In the

coreboot project, a set of

3rdpartysubmodules are available, with vendor blobs for init tasks on many boards. These must all be included in libreboot releases, even if unused. That way, even if the Libreboot build system does not yet integrate support for a given board, someone who downloads libreboot can still make changes to their local version of the build system, if they wish, to provide a configuration for their hardware.

Generally speaking, common sense is applied. For example, an exception to the minimalization might be if vendor raminit and libre raminit are possible, but the libre one is so broken so as to be unusable. In that situation, the vendor one should be used instead, because otherwise the user might switch back to an otherwise fully proprietary system, instead of using coreboot (via libreboot). Some freedom is better than none.

Libreboot's pragmatic policies will inevitably result in more people becoming coreboot developers in the future, by acting as that crucial bridge between it and non-technical people who just need a bit of help to get started.

Configuration

The principles above should apply to default configurations. However, libreboot is to be configurable, allowing the user to do whatever they like.

It's natural that the user may want to create a setup that is less libre than the default one in libreboot. This is perfectly acceptable; freedom is superior, and should be encouraged, but the user's freedom to choose should also be respected, and accomodated.

In other words, do not lecture the user. Just try to help them with their problem! The goal of the libreboot project is simply to make coreboot more accessible for otherwise non-technical users.

FREEDOM CATALOG

A freedom status page should also be made available, educating people about the software freedom status on each machine supported by the Libreboot build system. Please read: Software and hardware freedom status for each mainboard supported by Libreboot.

It is desirable to see a world where all hardware and software is libre, under the same ideology as the Libreboot project. Hardware!?

Yes, hardware. RISC-V is a great example of a modern attempt at libre hardware, often called Open Source Hardware. It is a an ISA for the manufacture of a microprocessor. Many real-world implementations of it already exist, that can be used, and there will only be more.

Such hardware is still in its infancy. We should start a project that will catalog the status of various efforts, including at the hardware level (even the silicon level). Movements like OSHW and Right To Repair are extremely important, including to our own movement which otherwise will typically think less about hardware freedoms (even though it really, really should!)

One day, we will live in a world where anyone can get their own chips made, including CPUs but also every other type of IC. Efforts to make homemade chip fabrication a reality are now in their infancy, but such efforts do exist, for example, the work done by Sam Zeloof and the Libre Silicon project:

- https://www.youtube.com/channel/UC7E8-0Ou69hwScPW1_fQApA

- http://sam.zeloof.xyz/

- https://libresilicon.com/

(Sam literally makes CPUs in his garage)

Problems with RYF criteria

Libreboot previously complied with FSF RYF criteria, but it now adheres to a much more pragmatic policy aimed at providing more freedom to more people, in a more pragmatic way. You can read those guidelines by following this URL:

- FSF Respects Your Freedom (RYF) guidelines: https://web.archive.org/web/20220604203538/https://ryf.fsf.org/about/criteria/

Put simply, the RYF guidelines pertain to commercial products, with the stipulation that they must not contain proprietary software, or known privacy issues like backdoors.

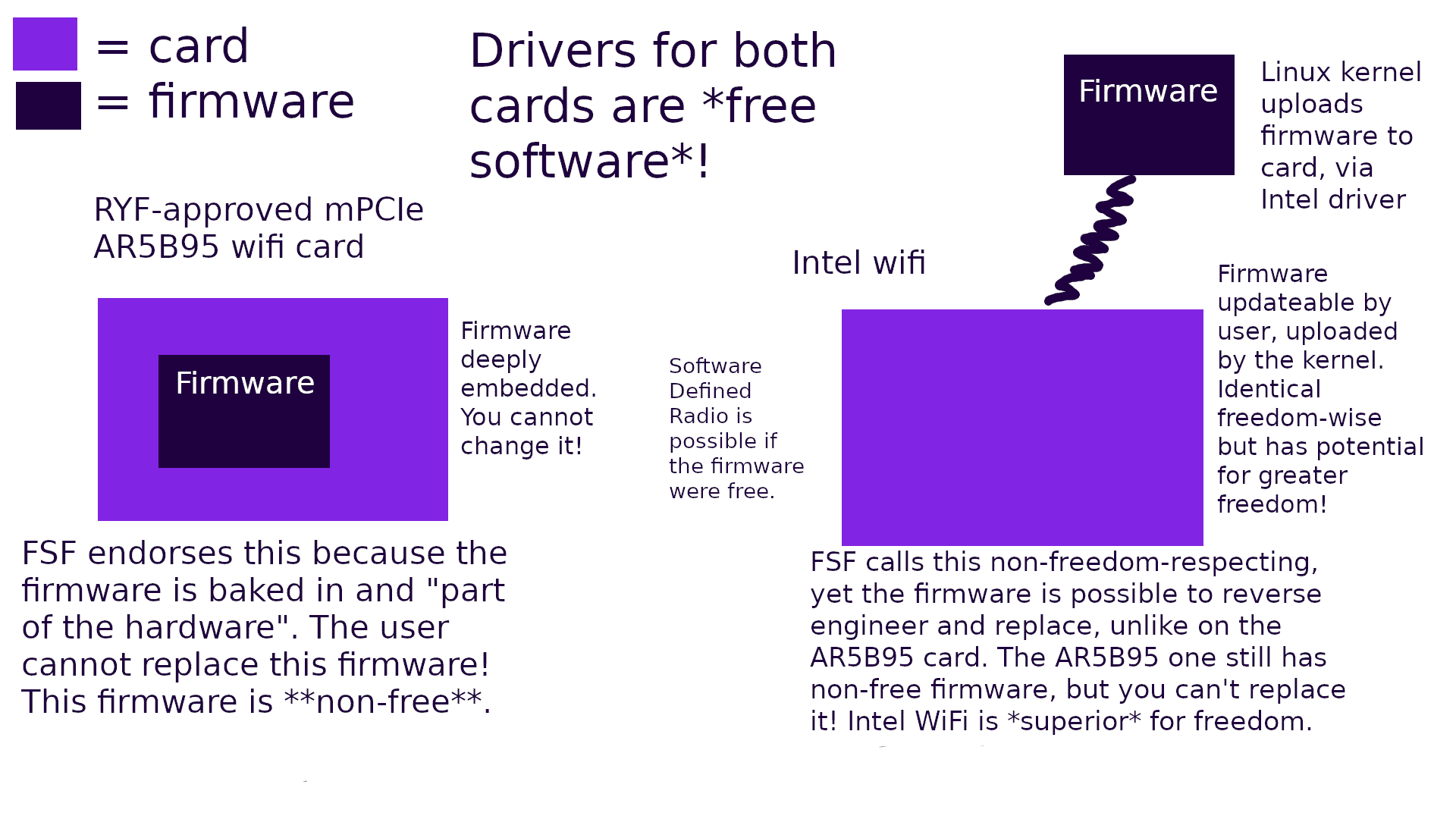

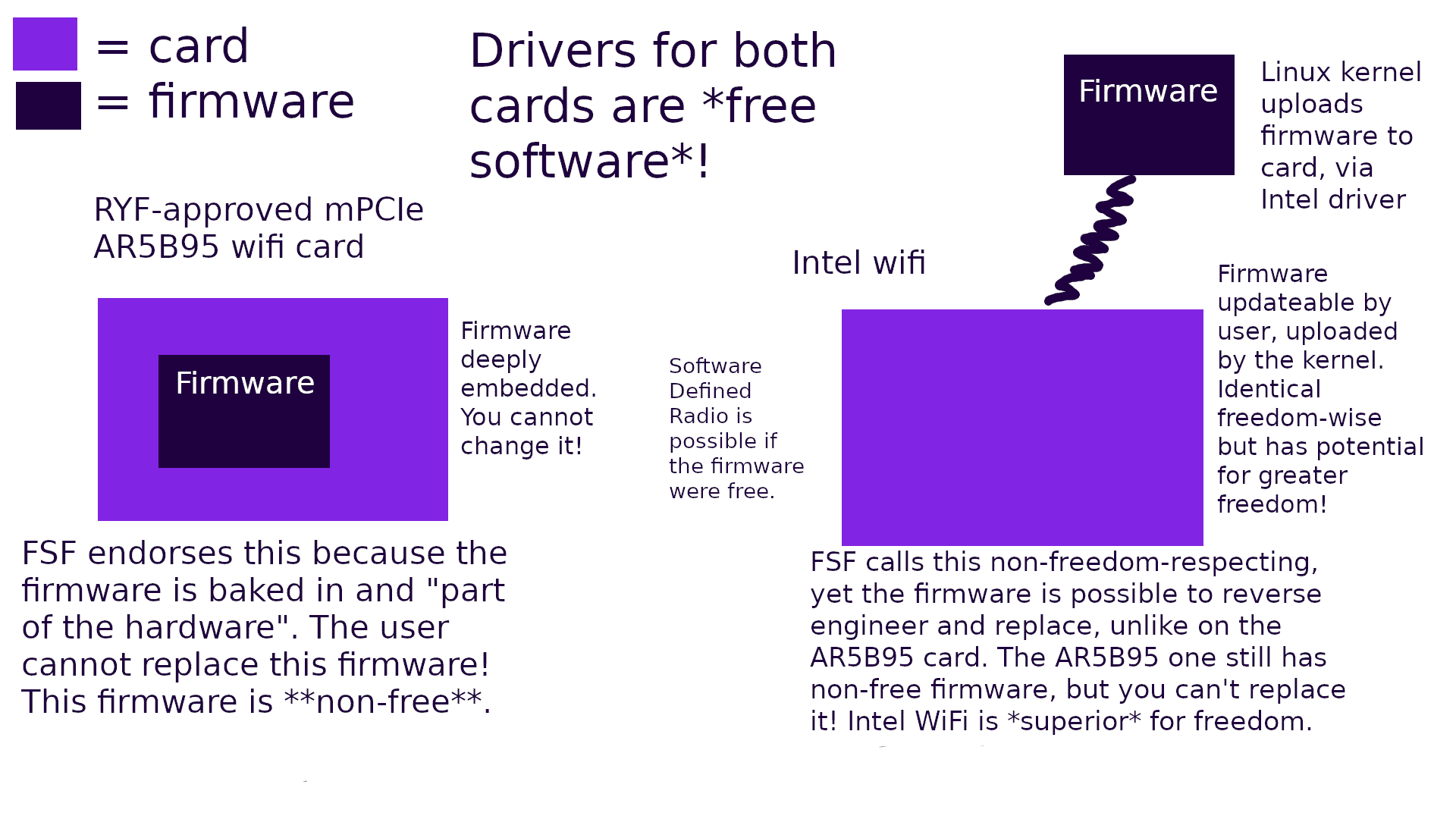

The total exclusion of all proprietary software is currently not feasible. For example, proprietary SDR firmware in WiFi chipsets, firmware in AHCI devices like HDDs or SSDs, and the like. The FSF RYF guidelines state the following exception, to mitigate this fact:

- "However, there is one exception for secondary embedded processors. The exception applies to software delivered inside auxiliary and low-level processors and FPGAs, within which software installation is not intended after the user obtains the product. This can include, for instance, microcode inside a processor, firmware built into an I/O device, or the gate pattern of an FPGA. The software in such secondary processors does not count as product software."

This should be rejected on ideological grounds. The rest of libreboot's policy and overall ideology expressed, in this article, will be based largely on that rejection. The definition of product software is completely arbitrary; software is software, and software should always be libre. Instead of making such exceptions, more hardware should be encouraged, with help given to provide as much freedom as possible, while providing education to users about any pitfalls they may encounter, and encourage freedom at all levels. When an organisation like the FSF makes such bold exceptions as above, it sends the wrong message, by telling people essentially to sweep these other problems under the rug, just because they involve software that happens to run on a "secondary processor". If the software is possible to update by the user, then it should be libre, regardless of whether the manufacturer intended for it to be upgraded or not. Where it really isn't possible to update such software, proprietary or not, advice should be given to that effect. Education is important, and the FSF's criteria actively discourages such education; it creates a false hope that everything is great and wonderful, just because the software on one arbitrary level is all perfect.

This view of the FSF's, as expressed in the quoted paragraph, assumes that there is primarily one main processor controlling your system. On many modern computers, this is no longer true.

Libre software does not exist in a vacuum, but we had less freedom in the past, especially when it came to hardware, so software was our primary focus.

The ability to study, adapt, share and use/re-use software freely is important, but there is a lot of nuance when it comes to boot firmware, nuance which is largely non-existent outside of firmware development, or kernel development. Most typical application/system software is high level and portable, but boot firmware has to be written for each specific machine, and due to the way hardware works, there are many trade-offs made, including by the FSF when defining what standards should apply in practise.

The fact that almost nobody talks about the EC firmware is because of the Respects Your Freedom certification. In reality, the EC firmware is crucial to user freedom, and ought to be free, but it is completely disregarded by the FSF as part of the hardware. This is wrong, and the FSF should actively encourage people to free it, on every laptop!

Other firmware currently outside the reach of the libreboot project are covered in the libreboot FAQ page. For example, HDD/SSD firmware is covered in the FAQ. Again, completely disregarded and shrugged off by the FSF.

The libreboot project will not hide or overlook these issues, because they are indeed critical, but again, currently outside the scope of what the Libreboot build system does. At the moment, the Libreboot build system concerns itself just with coreboot (and payloads), but this ought to change in the future.

Examples of FSF sweeping blobs under the rug

Over the years, there have been numerous cases where the FSF actively fails to provide incentive for levels of software freedom, such as:

- TALOS II "OpenPOWER" workstation from Raptor Engineering USA. It contains a broadcom NIC inside it which requires firmware, and that firmware was non-free. The FSF were willing to ignore it, and certify the TALOS II product under RYF, but Timothy Pearson of Raptor Engineering had it freed anyway, without being told to. Hugo Landau reverse engineered the specification and Evan Lojewski wrote libre firmware. See: See: https://www.devever.net/~hl/ortega and https://github.com/meklort/bcm5719-fw

- FSF once endorsed the ThinkPad X200, as sold by Minifree Ltd, which contains the Intel ME; the bootrom is still there, as is the ME coprocessor, but the ME is put into a disabled state via the Intel Flash Descriptor, and the ME firmware in flash is removed. However, the ME is an entire coprocessor which, with libre firmware, could be used for a great many things. In the Libreboot and coreboot projects, there has always been interest in this but the FSF disregards it entirely. The X200 product they certified came with Libreboot pre-installed.

- Libreboot has a utility written by I, Leah Rowe, that generates ICH9M flash descriptors and GbE NVM images from scratch. This is necessary to configure the machine, but these are binary blobs otherwise; the FSF would have been quite content to certify the hardware anyway since these were non-software blobs in a format fully documented by Intel (they are just binary configuration files), but I went ahead and wrote ich9gen anyway. With ich9gen, you can more easily modify the descriptor/gbe regions for your firmware image. See: https://libreboot.org/docs/install/ich9utils.html - libreboot also has this

- FSF once endorsed the ThinkPad T400 with Libreboot, as sold by Minifree. This machine comes in two versions: with ATI+Intel GPU, or only Intel GPU. If ATI GPU, it's possible to configure the machine so that either GPU is used. If the ATI GPU is to be used, a binary blob is needed for initialization, though the driver for it is entirely libre. The FSF ignored this fact and endorsed the hardware, so long as Libreboot does not enable the ATI GPU or tell people how to enable it. The Intel GPU on that machine has libre initialization code by the coreboot project, and a fully libre driver in both Linux and BSD kernels. In the configuration provided by Libreboot, the ATI GPU is completely disabled and powered down.

- All Libreboot-compatible ThinkPads contain proprietary Embedded Controller firmware, which is user-flashable (and intended for update by the manufacturer). The FSF chose to ignore the EC firmware, under their secondary processor exemption. See: http://libreboot.org/faq.html#ec-embedded-controller-firmware

In all of the above cases, the FSF could have been stricter, and bolder, by insisting that these additional problems for freedom were solved. They did not. There are many other examples of this, but the purpose of this article is not to list all of them (otherwise, a book could be written on the subject).

Problems with FSDG

The FSF maintains another set of criteria, dubbed Free System Distribution Guidelines (GNU FSDG)]

The FSDG criteria is separate from RYF, but has similar problems. FSDG is what the FSF-endorsed GNU+Linux distros comply with. Basically, it bans all proprietary software, including device firmware. This may seem noble, but it's extremely problematic in the context of firmware. Food for thought:

- Excluding vendor blobs in the linux kernel is bad. Proprietary firmware is also bad. Including them is a wiser choice, if strong education is also provided about why they are bad (less freedom). If you expose them to the user, and tell them about it, there is greater incentive (by simple reminder of their existence) to reverse engineer and replace them.

- Firmware in your OS kernel is good. The FSF simultaneously gives the OK for hardware with those same binary blobs if the firmware is embedded into a ROM/flash chip on the device, or embedded in some processor. If the firmware is on separate ROM/flash, it could still be replaced by the user via reverse engineering, but then you would probably have to do some soldering (replace the chip on the card/device). If the firmware is loaded by the OS kernel, then the firmware is exposed to the user and it can be more easily replaced. FSF criteria in this regard encourages hardware designers to hide the firmware instead, making actual (software) freedom less likely!

Besides this, FSDG seems OK. Any libre operating system should ideally not have proprietary drivers or applications.

Hardware manufacturers like to shove everything into firmware because their product is often poorly designed, so they later want to provide workarounds in firmware to fix issues. In many cases, a device will already have firmware on it but require an update supplied to it by your OS kernel.

The most common example of proprietary firmware in Linux is for wifi devices. This is an interesting use-case scenario, with source code, because it could be used for owner-controlled software defined radio.

The Debian way is ideal. The Debian GNU+Linux distribution is entirely libre by default, and they include extra firmware if needed, which they have in a separate repository containing it. If you only want firmware, it is trivial to get installer images with it included, or add that to your installed system. They tell you how to do it, which means that they are helping people to get some freedom rather than none. This is an inherently pragmatic way to do things, and it's now how Libreboot does it.

More context regarding Debian is available in this blog post: https://blog.einval.com/2022/04/19#firmware-what-do-we-do - in it, the author, a prominent Debian developer, makes excellent points about device firmware similar to the (Libreboot) article that you're reading now. It's worth a read! As of October 2022, Debian has voted to include device firmware by default, in following Debian releases. It used to be that Debian excluded such firmware, but allowed you to add it.

OpenBSD is very much the same, but they're clever about it: during the initial

boot, after installation, it tells you exactly what firmware is needed and

updates that for you. It's handled in a very transparent way, by

their fw_update program which you can read about here:

https://man.openbsd.org/fw_update

Banning linux-firmware specifically is a threat to freedom in the long term, because new users of GNU+Linux might be discouraged from using the OS if their hardware doesn't work. You might say: just buy new hardware! This is often not possible for users, and the user might not have the skill to reverse engineer it either.

More detailed insight about microcode

To be clear: it is preferable that microcode be libre. The microcode on Intel and AMD systems are proprietary. Facts and feelings rarely coincide; the purpose of this section is to spread facts.

The libreboot build system now enables microcode updates by default.

Not including CPU microcode updates is an absolute disaster for system stability and security.

Making matters worse, that very same text quoted from the FSF RYF criteria in fact specifically mentions microcode. Quoted again for posterity:

"However, there is one exception for secondary embedded processors. The exception applies to software delivered inside auxiliary and low-level processors and FPGAs, within which software installation is not intended after the user obtains the product. This can include, for instance, microcode inside a processor, firmware built into an I/O device, or the gate pattern of an FPGA. The software in such secondary processors does not count as product software."

Here, it is discussing the microcode that is burned into mask ROM on the CPU itself. It is simultaneously not giving the OK for microcode updates supplied by either coreboot or the Linux kernel; according to the FSF, these are an attack on your freedom, but the older, buggier microcode burned into ROM is OK.

The CPU already has microcode burned into mask ROM. The microcode configures logic gates in the CPU, to implement an instruction set, via special decoders which are fixed-function; it is not possible, for example, to implement a RISCV ISA on an otherwise x86 processor. It is only possible for the microcode to implement x86, or broken x86, and the default microcode is almost always broken x86 on Intel/AMD CPUs; it is inevitable, due to the complexity of these processors.

The FSF believes that these x86 microcode updates (on Intel/AMD) allow you to completely create a new CPU that is fundamentally different than x86. This is not true. It is also not true that all instructions in x86 ISA are implemented with microcode. In some cases, hardcoded circuitry is used! The microcode updates are more like tiny one liner patches here and there in a git repository, by way of analogy. To once again get in the head-space of the FSF: these updates cannot do the CPU equivalent of re-factoring an entire codebase. They are hot fixes, nothing more!

Not including these updates will result in an unstable/undefined state. Intel themselves define which bugs affect which CPUs, and they define workarounds, or provide fixes in microcode. Based on this, software such as the Linux kernel can work around those bugs/quirks. Also, upstream versions of the Linux kernel can update the microcode at boot time (however, it is recommend still to do it from coreboot, for more stable memory controller initialization or “raminit”). Similar can be said about AMD CPUs.

Here are some examples of where lack of microcode updates affected Libreboot, forcing Libreboot to work around changes made upstream in coreboot, changes that were good and made coreboot behave in a more standards-compliant manner as per Intel specifications. Libreboot had to break coreboot to retain certain other functionalities, on some GM45/ICH9M thinkpads:

These patches revert bug fixes in coreboot, fixes that happen to break other functionality but only when microcode updates are excluded. The most technically correct solution is to not apply the above patches, and instead supply microcode updates!

Pick your poison. Not adding the updates is irresponsible, and ultimately futile, because you still end up with proprietary microcode, but you just get an older, buggier version instead!

This shift in project policy does not affect your freedom at all, because you still otherwise have older, buggier microcode anyway. However, it does improve system reliability by including the updates!

Such pragmatic policy is superior to the dogma that Libreboot users once had to endure. Simply put, the Libreboot project aims to give users as much freedom as is possible for their hardware; this was always the case, but this mentality is now applied to [a lot] more hardware.

Other considerations

Also not covered strictly by Libreboot: OSHW and Right To Repair. Freedom at the silicon level would however be amazing, and efforts already exist; for example, look at the RISCV ISA (in practise, actual fabrication is still proprietary and not under your control, but RISCV is a completely libre CPU design that companies can use, instead of having to use proprietary ARM/x86 and so on). Similarly, Right To Repair (ability to repair your own device, which implies free access to schematics and diagrams) is critical, for the same reason that Libre Software (Right To Hack) is critical!

OSHW and Right To Repair are not covered at all by RYF (FSF's Respects Your Freedom criteria), the criteria which Libreboot previously complied with. RYF also makes several concessions that are ultimately damaging, such as the software as circuitry policy which is, frankly, nonsensical. ROM is still software. There was a time when the FSF didn't consider BIOS software a freedom issue, just because it was burned onto a mask ROM instead of flashed; those FSF policies ignore the fact that, with adequate soldering skills, it is trivial to replace stand-alone mask ROM ICs with compatible flash memory.

Conclusion

RYF isn't wrong per se, just flawed. It is correct in some ways and if complied with, the result does give many freedoms to the user, but RYF completely disregards many things that are now possible, including freedoms at the hardware level (the RYF criteria only covers software). Those guidelines are written with assumptions that were still true in the 1990s, but the world has since evolved. The libreboot project rejects those policies in their entirety, and instead takes a pragmatic approach.

The conclusion that should be drawn from all of this is as follows:

Following FSF criteria does not damage anything, but that criteria is very conservative. Its exemptions should be disregarded and entirely ignored. RYF is no longer fit for purpose, and should be rewritten to create a more strict set of guidelines, without all the loopholes or exemptions. As has always been the case, Libreboot tries to always go above and beyond, but the Libreboot project does not see RYF as a gold standard. There are levels of freedom possible now that the RYF guidelines do not cover at all, and in some cases even actively discourage/dis-incentivize because it makes compromises based on assumptions that are no longer true.

Sad truth: RYF actively encourages less freedom, by not being bold enough. It sets a victory flag and says mission accomplished, despite the fact that the work is far from complete!

If followed with exemptions unchallenged, RYF may in some cases encourage companies to sweep under the rug any freedom issues that exist, where it concerns proprietary firmware not running on the host CPU (such as the Embedded Controller firmware).

I propose that new guidelines be written, to replace RYF. These new guidelines will do away with all exemptions/loopholes, and demand that all software be libre on the machine, or as much as possible. Instead of only promoting products that meet some arbitrary standard, simply catalog all systems on a grand database of sorts (like h-node.org, but better), which will define exactly what hardware and software issues exist on each device. Include Right to Repair and OSHW (including things like RISCV) in the most "ideal" standard machine; the gold standard is libre silicon, like what Sam Zeloof and others are working on nowadays.

This new set of criteria should not attempt to hide or ignore anything. It should encourage people to push the envelope and innovate, so that we can have much more freedom than is currently possible. Necessity is the mother of all invention, and freedom is an important goal in every aspect of life, not just computing.

Don't call it "Respects Your Freedom" or something similar. Instead, call it something like: the freedom catalog. And actually focus on hardware, not just software!

Other resources

Ariadne Conill's RYF blog post

Ariadne Conill, security team chair of Alpine Linux, posted a very robust article about RYF, with similar points made when compared to this article. However, Ariadne goes into detail on several other examples of problems with the FSF RYF criteria; for example, it talks about the Novena product by Bunnie.

It's worth a read! Link: